A descendant of an ancient Mayan tribe in Guatemala, Erik Yax Garcia grew up in a place where education is barely valued.

His hometown, Paraje Pacajac Cantón Panquix, sits near the top of a mountain, isolated from the nearest city, Totonicapán, which lies about an hour’s drive away. The entire community speaks only K’iche’ (pronounced “key-chay”), one of several Mayan dialects, and while the land is rich in dense forests, mountain streams, and lush grass, most families are poverty-stricken, with as many as eight or nine family members living in the same one- or two-room home.

Like many Mayan ancestors, they live in homes made primarily of adobe, or sometimes adobe and wooden logs. Given the high price and instability of electricity, few homes have modern stoves, refrigerators, or even running water. While simple pipes may be set up to run water from nearby mountain streams, most families carry buckets of water to fill their sinks.

Growing vegetables to sell a few days a week in the city can be one source of income in this agricultural community. Chopping wood from the forest, or construction work—with wood or adobe—is yet another, and some families attempt to do all of those things. Erik’s family—one of the lucky ones—was able to scrape together enough money to purchase a truck for the trips to sell goods in the city, rather than the age-old practice of transporting wares by horse or donkey.

“I didn’t want to be like my parents, who do the same thing every day and struggle and struggle,” he explains. “I used to tell this to my younger brother, and he’d laugh. But I’d say, ‘My life is going to be different,’ and he wouldn’t believe it.”

Perhaps his brother had good reason.

Time in Guatemala

In Erik’s hometown, most parents don’t have the finances needed for children’s school uniforms, books, or transportation. As a result, children often end up working at ages as young as 10 or 12. While girls will frequently return home to prepare for housekeeping and marriage at an early age, boys may work under the instruction of older friends or neighbors to learn a trade, but there are no training manuals or courses, he says. Not surprisingly, the rate of illiteracy is high, with nearly 20 percent of males and about 15 percent of females ages 15–24 illiterate, according to UNICEF.

“Other communities are even worse; their poverty is awful. The kids have no education, they have no homes. I know how it feels when you don’t have the opportunities that others have. It looks like there’s no way forward and nobody tells you anything to encourage you,” he describes.

Erik himself stopped attending school in Guatemala at 15.

“I left my community when I was very young,” he says. “I went to the city to get a job, and that’s when I started learning Spanish, interacting with people in the main city, but it wasn’t enough. There was corruption and violence and I didn’t like the city. I was tired of everything. I heard about the U.S. and heard it’s really hard, but I was willing to take a risk. I didn’t think about it for a long time. I said, ‘I’m going,’ and the next week I left.”

Journey to the United States

It was 2010. He was 17, and alone in a strange country.

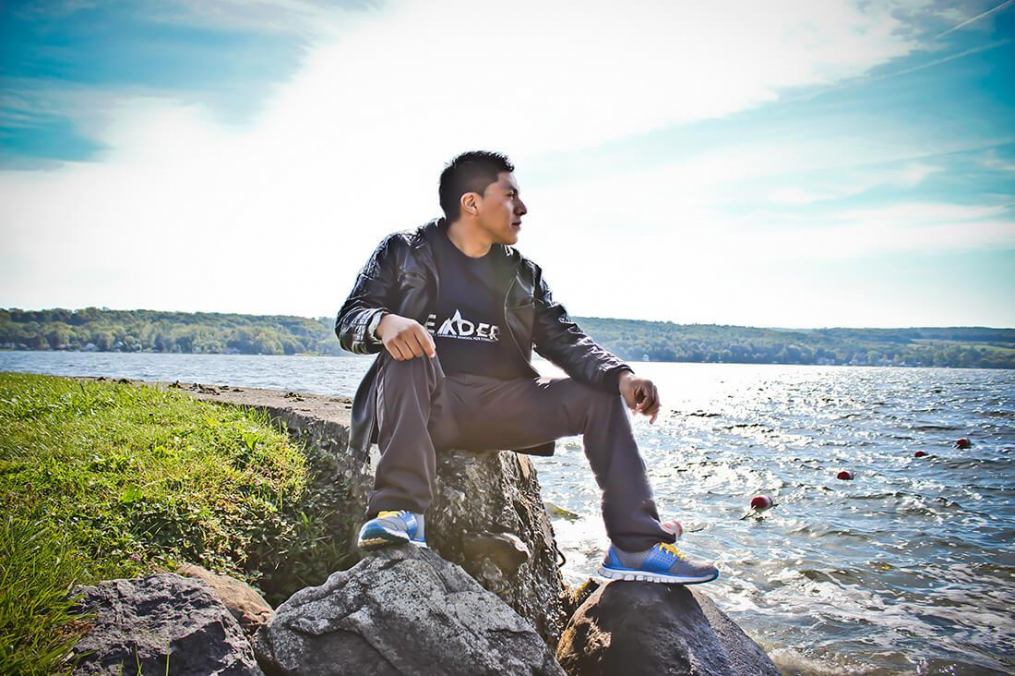

Briefly detained in Texas before his case for permanent residency was heard, Erik scraped together what money he could to fly to New York City, landing with a little more than $150 and still struggling with the English language. He wound up in Brooklyn, at the Expeditionary Community School for Leaders, a public school where many international students—including those from Pakistan, Russia, and other countries—attend. A kindhearted English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher learned about Erik’s solitary situation and invited him to stay in her family’s home. And while appreciative, Erik says, “I didn’t feel comfortable living there, because I was so used to being independent and not relying on people.” So about a year after the initial invitation, Erik moved out, choosing instead to work and attend high school at the same time.

“I had different jobs. I worked in restaurants, bakeries…sometimes I would have two jobs,” Erik says. “I have a cousin who lives in Brooklyn, and I asked him to help me by sharing an apartment because I wanted to keep on with my education. I wouldn’t have had a problem working. I’d have a happy life, but without an education, I cannot help poor kids in need.”

In 2013, Erik graduated from high school and began exploring colleges, looking for schools in rural areas, especially upstate New York, because of growing up in a community “very connected to the environment, natural areas, trees, birds, and animals,” he describes. “I missed that, and New York City is a very different environment from that. I wanted to balance my life. I applied to 19 colleges and I got accepted to almost all of them, but I really liked Keuka College. It’s small—it feels like a community to me.”

A Mission to Make Change

After completing his first year as an environmental science major, Erik changed his major to political science and history, with a goal to “make changes in the future, to create policies that will help poor people in my hometown.”

“Erik was very deliberate and cautious about his switch to political science, and I think this attests to the thought that he has given to his future and his commitment to his goal of finding the best way that someone like him can make a difference in the world,” says Dr. Angela Narasimhan, assistant professor of political science.

Erik sees education as a primary goal, and says he hopes someday to return to his hometown, armed with education, technology, and fluency in Spanish, to help those in his native community understand that they, too, can have a better life.

“I would like to create a nonprofit organization where people will give money and sponsor a child so they can have an education,” Erik says. “It’s very cheap in U.S. dollars, but for Guatemalans, they cannot afford it.”

Ultimately, Erik believes that if his native people can be educated, they can be better informed about the resources and options available to them, which can help them preserve their culture, yet do so with economic efficiencies, thereby improving life for everyone. He sees this principle applying in the political area as well as in the environment. Those in the mountains can learn how to conserve forests by planned growth to replace trees cut down for sale for fuel or construction, for example. And rather than placing false hopes in corrupt officials who make empty promises, education and information can better sustain the people, Erik believes.

According to him, it’s common for political leaders to promise to fix roads or build a school, but “they do it just to get votes,” and then later, the leaders seem to have forgotten their promises and “are not doing anything for the people,” he says.

In contrast to the U.S., there is no access to mass media to discover a politician’s record, and those living in the mountains have to travel in groups to the city to vote, which means, “it’s more about populism,” Erik says, as the poorest in a community vote for the same person their neighbor supports. One of the reasons Erik is placing a high value on Spanish and has enrolled in Spanish courses at Keuka College is to improve in a language necessary to win elections. Erik didn’t know Spanish as a child, and only began picking it up only after leaving home. But to accomplish his goal to educate his native community members about voting rights and different types of government, “and to help them to get to know the president and what they are voting for,” he says he knows the Spanish language will be important.

“If we educate the people about how the political system works in Guatemala, they will be able to make decisions and choose the right leaders,” he said. “That’s why they need more education. I’m taking advantage of all the opportunities I can because I want to share it with the people who are still in my community there, and I want to motivate them.”

To that end, he hopes to make a return trip to Guatemala soon, possibly as early as this summer, to learn more about the community history, to interview its elder leaders, and to start visiting schools to observe how teachers there are handling education now and what additional support they may need to keep improving it. In the meantime, he spends College breaks back in New York City, working and improving his Spanish. Last summer, for his Field Period™, Erik visited a middle school to teach students about water quality, and also provided translation for kayaking programs offered to large Hispanic populations in New York City.

“I feel so good when people that cannot speak English come to me for help with translation,” he says. “I was able to share a lot of things with them.”

For someone who hails from another country, but who has proved his belief in the American Dream, Erik Yax Garcia also appears to have adopted something else familiar to many in the Keuka College family: the Keuka spirit.

“Sometimes it’s really hard, and I could complain, but I start thinking, if I didn’t grow up that way, I wouldn’t think the way I think now. That makes me happy and I feel lucky,” Erik says.